Activists often find themselves in a battle against other like-minded changemakers.

And they fight ruthlessly to maximize their gains.

It’s a war of optimization.

Here’s what I mean:

Each changemaker has their own issue of specialty and is promoting what they believe to be the optimal solution.

For example, advocates around the country are lobbying for multi-billion dollar investments to build new, Affordable Housing.

Criminal justice activists are introducing a wide range of new (and expensive) neighborhood initiatives.

And anti-poverty organizations are relentlessly pressing for significant increases in welfare program spending.

Each promotes a compelling case based on maximizing impact.

“Full investment – right now – will result in the best outcomes!”

But not everyone can get what they want.

You see, communities almost never have the time or resources to fully implement each problem’s optimal solution.

In this environment of dueling changemakers, even the most well-meaning leaders can get confused about what to do.

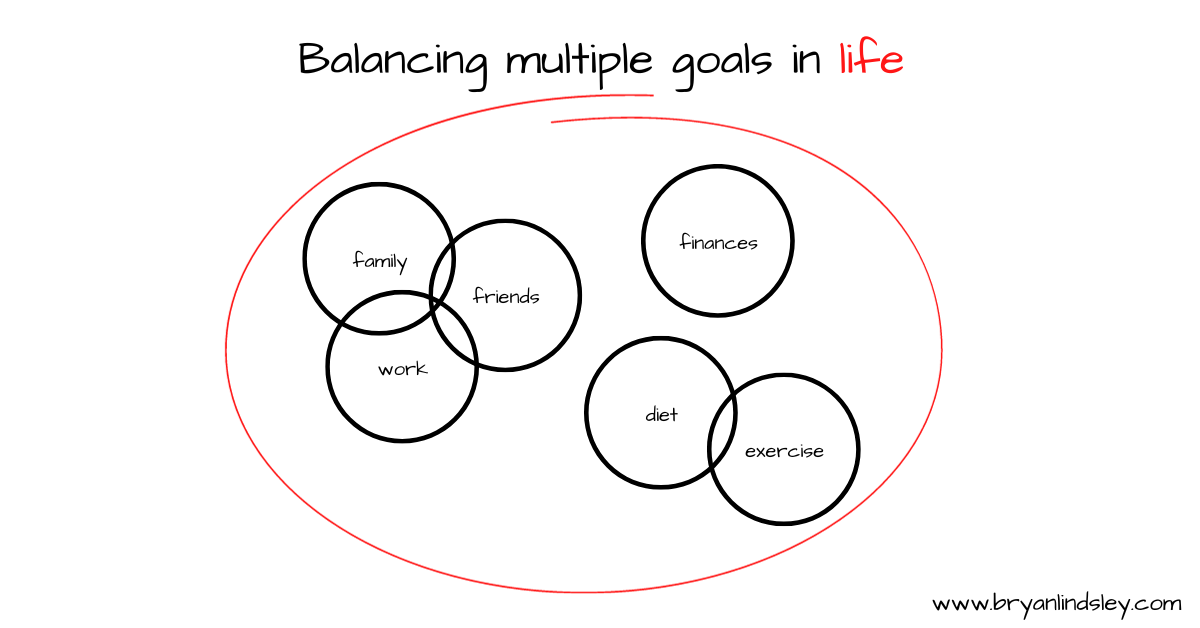

Insights from competing interests in your personal life

Let’s compare this social policy conundrum to our personal lives.

In some sense, we already know we can’t have it all.

Optimizing any one part of ourselves – like always doing everything to advance professionally – takes a huge toll on other areas, like family obligations and our health.

Through trial and error, we find that we must satisfice (a combination of satisfy and suffice) across work, family, health, and fulfillment.

In other words, we don’t fully maximize or choose the optimal solution in any one area.

Rather, we try to achieve the minimum requirements across many domains.

By balancing and aligning many suboptimal choices – for work, for family, for health – we find that we can optimize our lives.

For example, we work late one night per week to get ahead, but make sure we can pick up our kids from school the other days of the week.

We choose the not-as-nice neighborhood gym rather than the state-of-the-art CrossFit facility across town because it means that workouts take less time and leave room for taking our kids to soccer practice.

We sadly forgo having the healthiest of salads every night of the week in favor of dinners with somewhat healthy foods that our kids will still eat.

I could go on…

But my point is that the right combination of suboptimal choices – especially the relationship of how they align, fit and synergize across the parts – optimizes the whole.

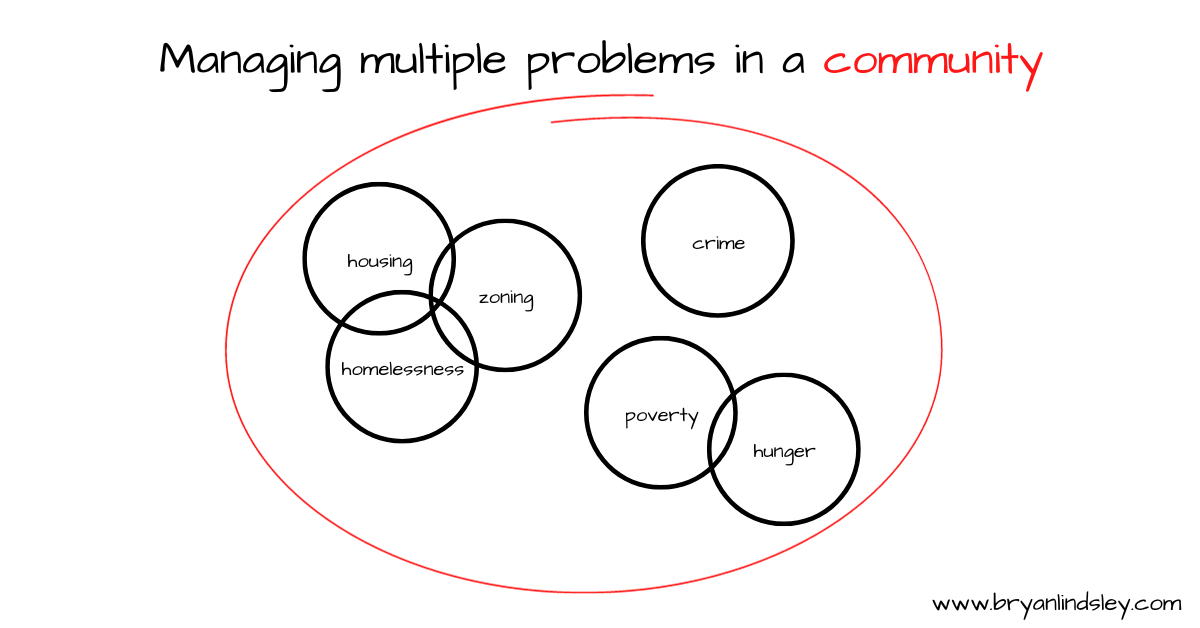

How optimal solutions can suboptimize community outcomes

Now, let’s apply this wisdom to the pressing issues of affordable housing and homelessness in our communities.

Housing advocates argue that housing is the most pressing social issue right now.

Their optimal answer is colossal government investments to build Affordable Housing.

But there’s a catch: the housing market is massive, and billion-dollar investments are just drops in the ocean when it comes to housing affordability.

To give a realistic sense of scale, the market cap of housing in some big cities tops $1 trillion.

The truth is that housing alone could consume social service budgets for a decade and still not significantly impact market housing and rental prices.

And while a billion dollars is small compared to the housing market, it’s huge compared to government budgets for addressing the full range of tough social problems.

We must admit that housing affordability, just like any community problem we face, is only one piece of an intricate puzzle that includes other important problems.

The danger for our communities lies in focusing on a single problem to the detriment of others.

Don’t solve problems. Manage messes.

Optimal solutions are often so huge that they tend to block out the view of other problems.

That’s because proponents believe that they will solve their problem once and for all.

“This investment in Affordable Housing will end homelessness. And then we can focus on other issues.”

And yet, most social problems – poverty, crime, homelessness – aren’t ever truly solved.

This is sort of like the examples above from our personal lives.

You don’t solve “work.”

You don’t solve “family.”

For all of these issues, the answer lies not in trying to solve them, but in managing them.

As systems theorist Russell Ackoff prophetically counseled leaders who must grapple with complex problems and messes:

“Managers do not solve problems, they manage messes.”

How?

We can apply the same systems thinking insights we used for optimizing our lives:

- To manage a mess of interrelated problems we must try to achieve the minimum requirements across many domains.

- The right combination of suboptimal choices – especially the relationship of how they align, fit and synergize across the parts – optimizes the whole.

So get out there and advocate for change – just do it with all the balance and pragmatism you bring to your personal life.

See you next week.

==

Whenever you’re ready, there are two ways I can help you:

→ I’m a strategic advisor for the toughest societal problems like poverty, crime and homelessness. People come to me when they want to stop spinning their wheels and get transformative, systems-level change.

→ I’m a coach for emerging and executive leaders in the social and public sectors who want to make progress on their biggest goals and challenges.

Let’s find out how I can help you become transformational.